이기영

M’VOID is a program that plans and presents exhibitions of leading artists at home and abroad who question contemporary aesthetic values while strengthening their works with insights.

ABOUT

서울대학교 미술대학 동양화과, 동 대학원 졸업

現 이화여자대학교 조형예술대학 동양화 전공 교수

SOLO Exhibition (selected)

2025 |

밝은 곳에 서있다, 갤러리밈, 서울 |

2023 |

두번째 답변, 이화익갤러리, 서울 |

2022 |

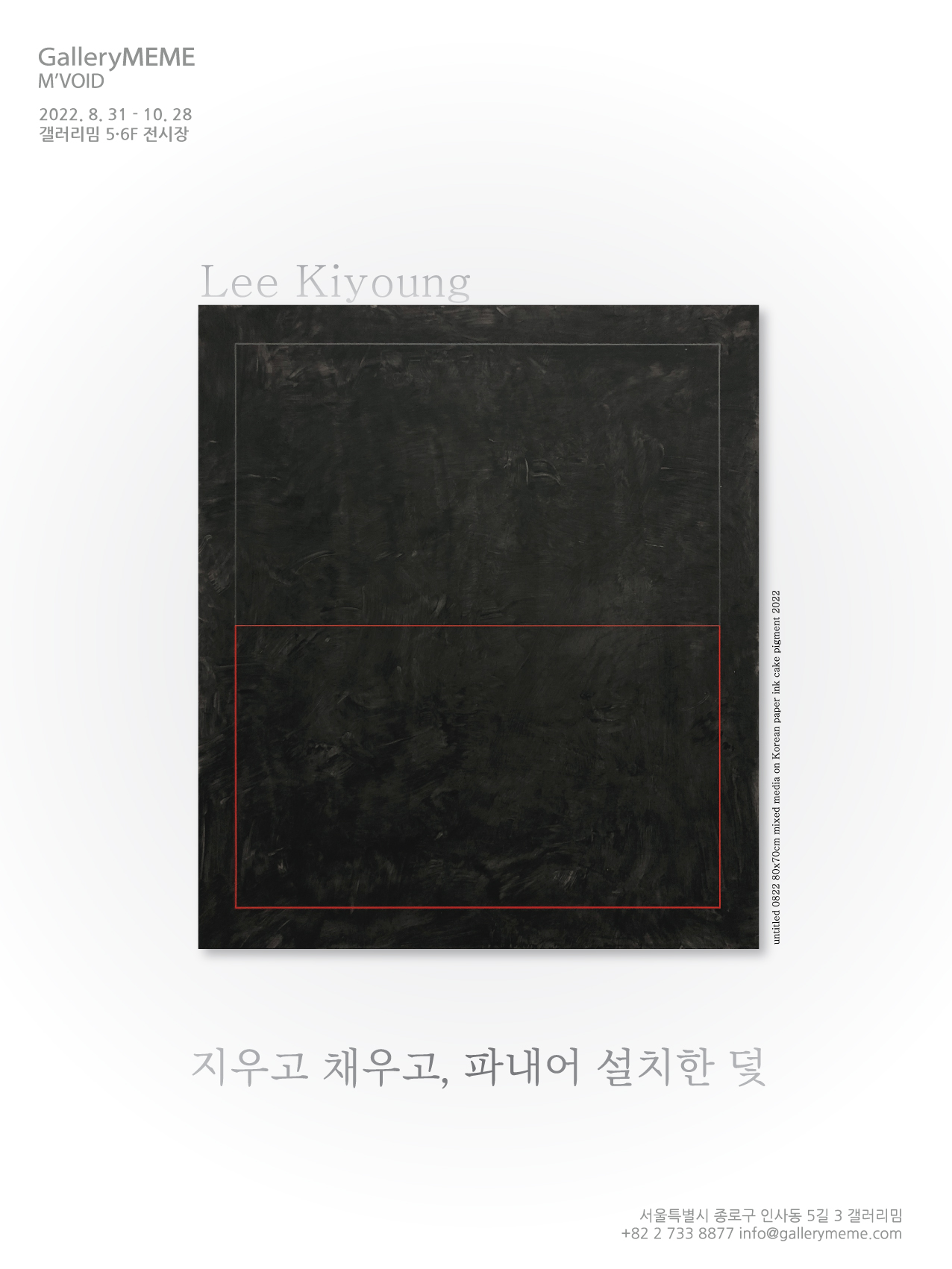

지우고 채우고, 파내어 설치한 덫, 갤러리밈, 서울 |

2019 |

이기영 개인전, ANA갤러리, 서울 |

2018 |

LEE KIYOUNG WORKS, 이화익갤러리, 서울 |

2017 |

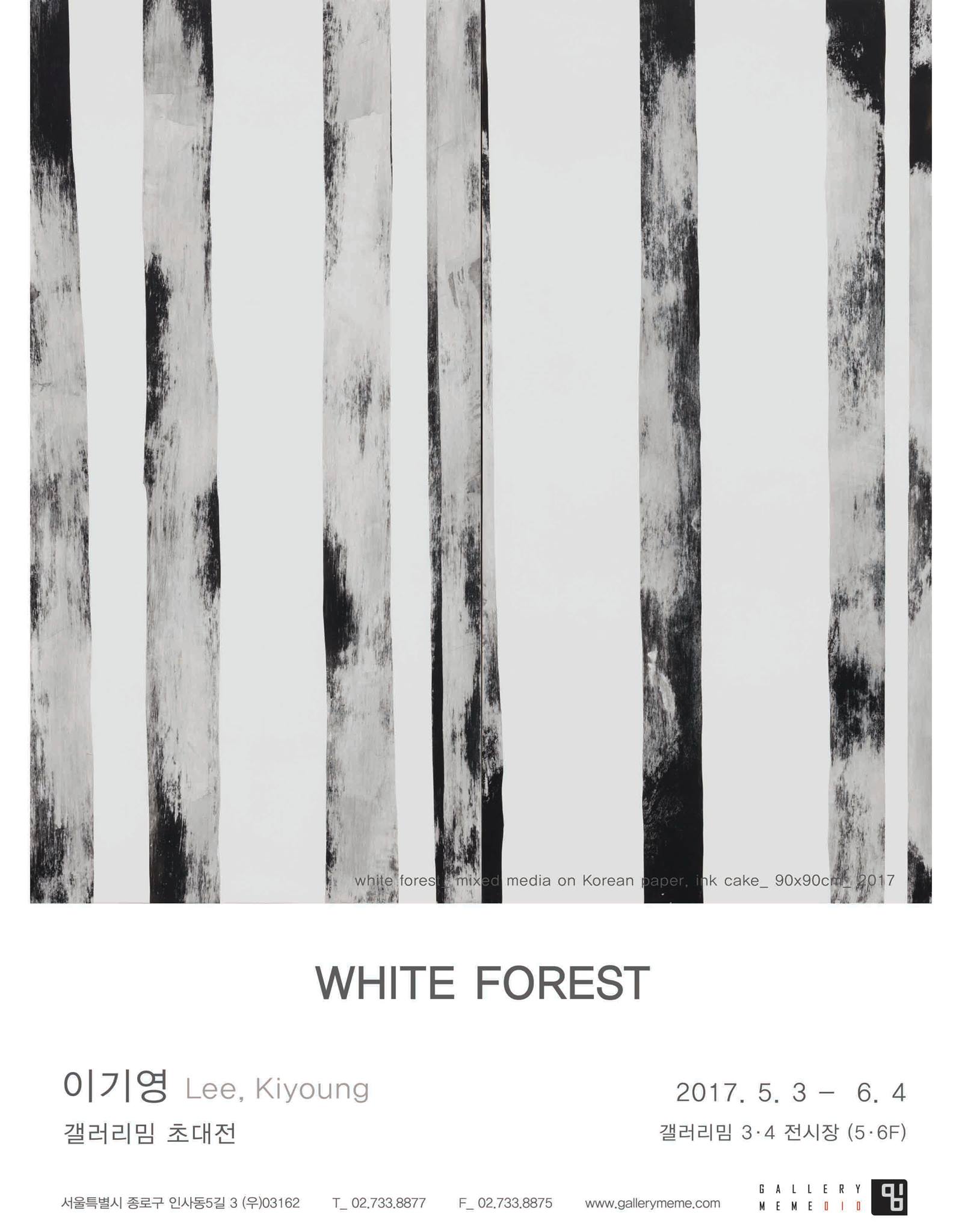

White Forest, 갤러리밈, 서울 |

2016 |

지우고 지우다, 갤러리 플래닛, 서울 |

2014 |

이기영展, 갤러리 플래닛, 서울 |

2011 |

MAD Museum of Art & Design, 싱가폴 |

2010 |

Zone Contemporary Art, 뉴욕 2006 갤러리 21+Yo, 도쿄 |

2004 |

이기영 展, 금산갤러리, 서울 |

GROUP Exhibition (selected)

2021 |

이화익갤러리 20주년 기념 전시, 이화익갤러리, 서울 |

2017 |

보통만큼의 빛과 공기, 예술의 기쁨, 김세중미술관, 서울 |

2015 |

세븐 사인즈, 박수근미술관, 강원 |

2010 |

Diversity at play, Museum of Art & Design, 싱가폴 |

2008 |

이기영, 이수경 2인전, 이화익갤러리, 서울 |

2003 |

동양화 Paradiso, 포스코 미술관, 서울 |

2002 |

한국현대미술 중남미 4개국 순방전, 에콰도르/페루/아르헨티나/멕시코 |

|

Today's Korean painting, CASO, 일본 |

2000 |

젊은 모색 2000, 국립현대 미술관, 과천 |

Collections

국립현대미술관 미술은행, 서울시립미술관, 경기도립미술관, 과천 국립현대미술관, 이스라엘 주재 한국대사관, 핀란드 주재 한국 대사관, 이화재단, 경기문화재단, 법무법인 태평양 외 다수 작품 소장

생성으로 향하는 여정

불연속적 평면

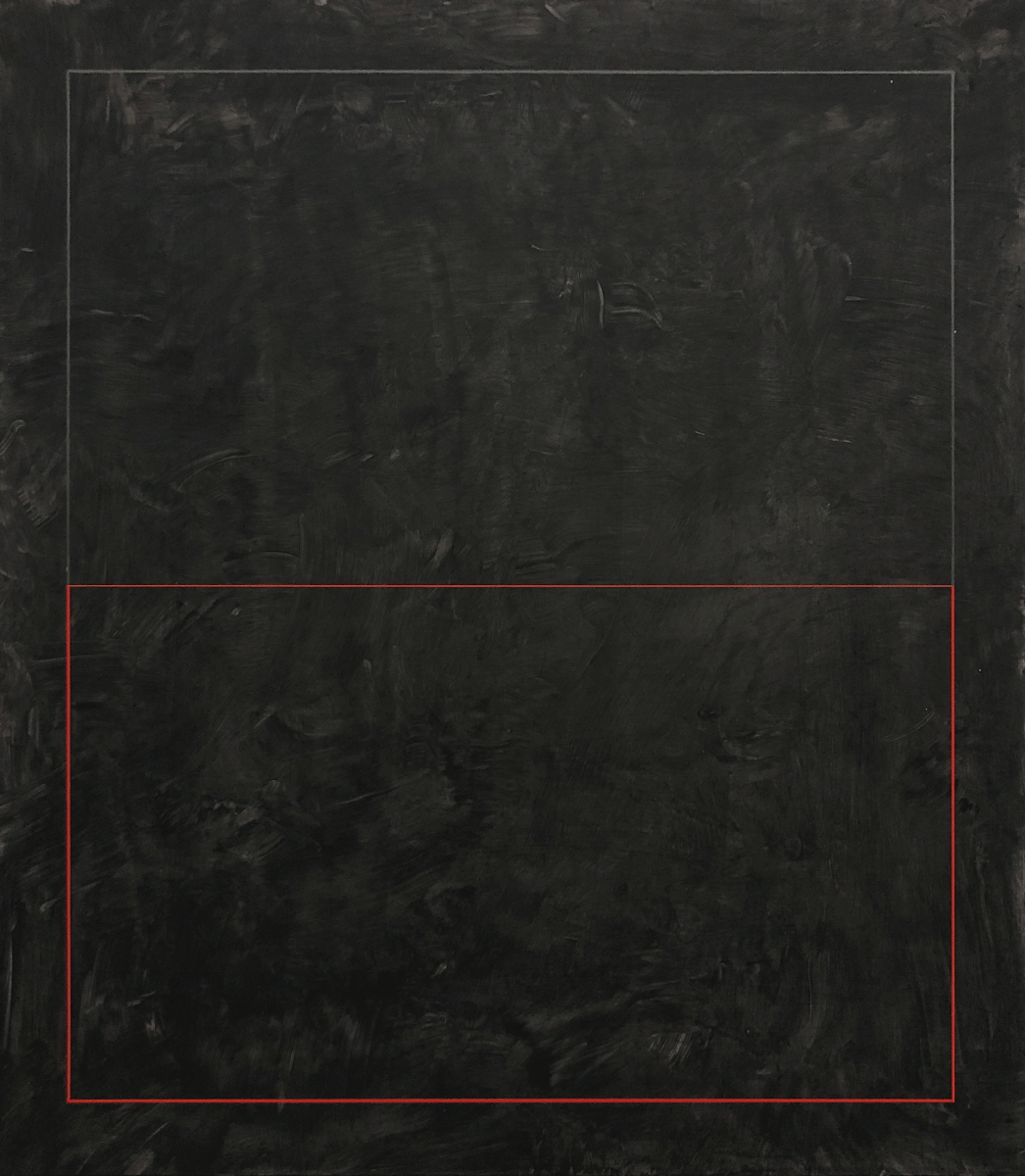

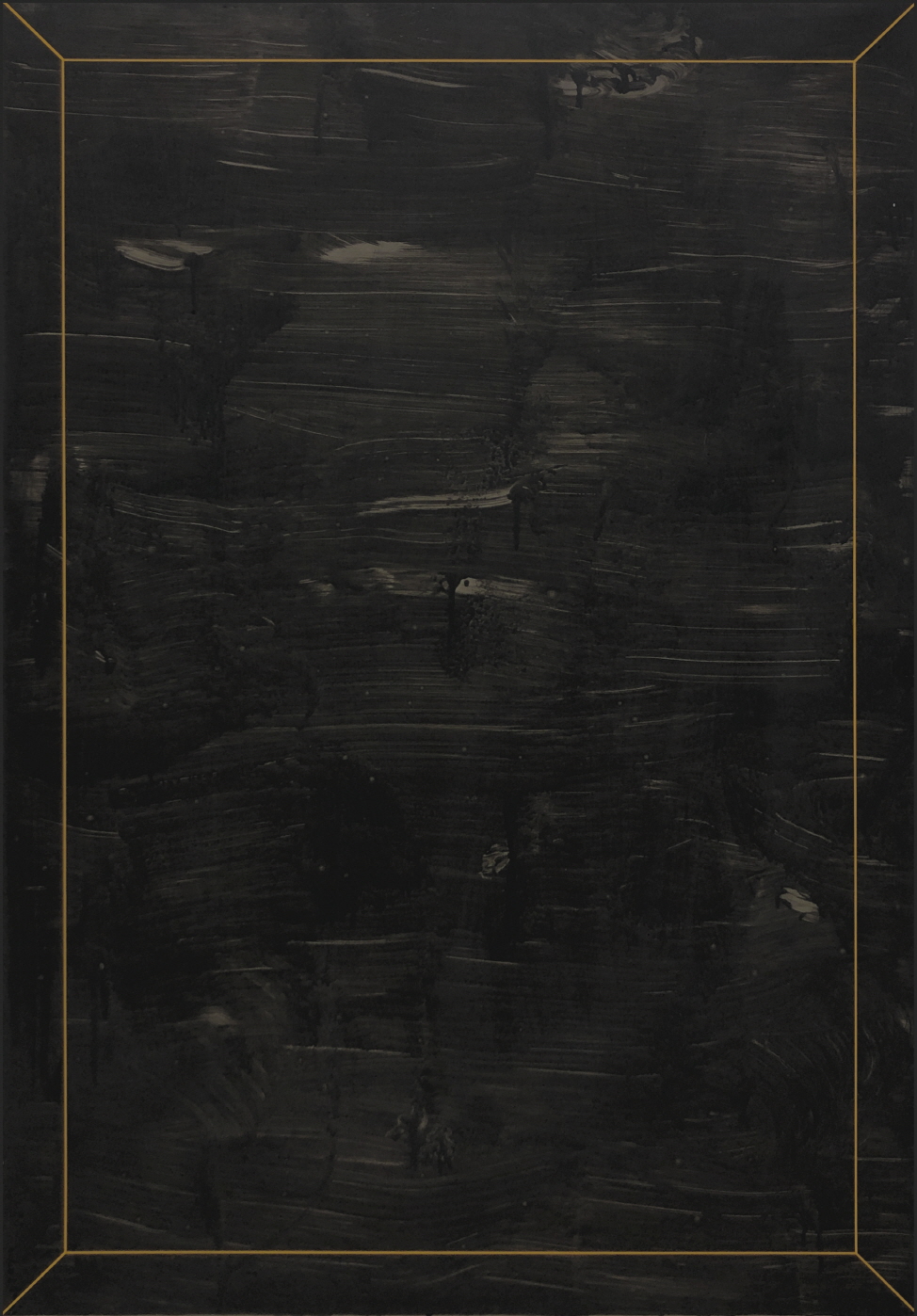

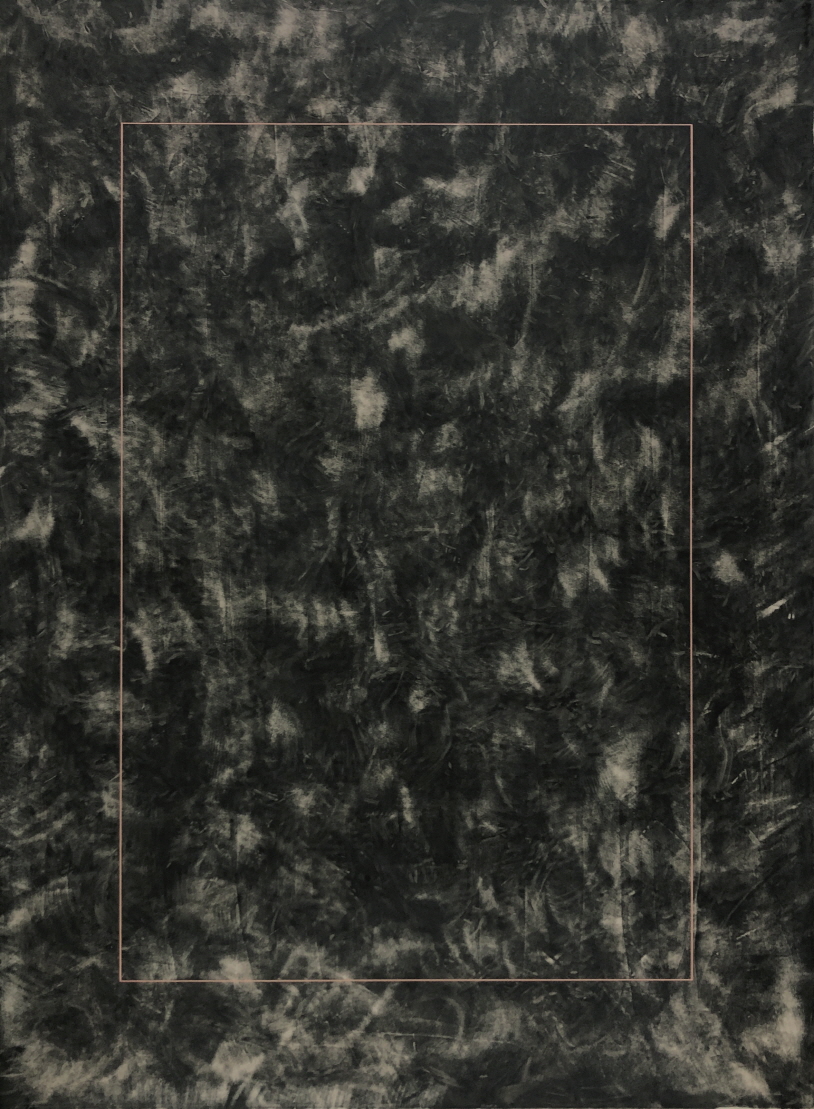

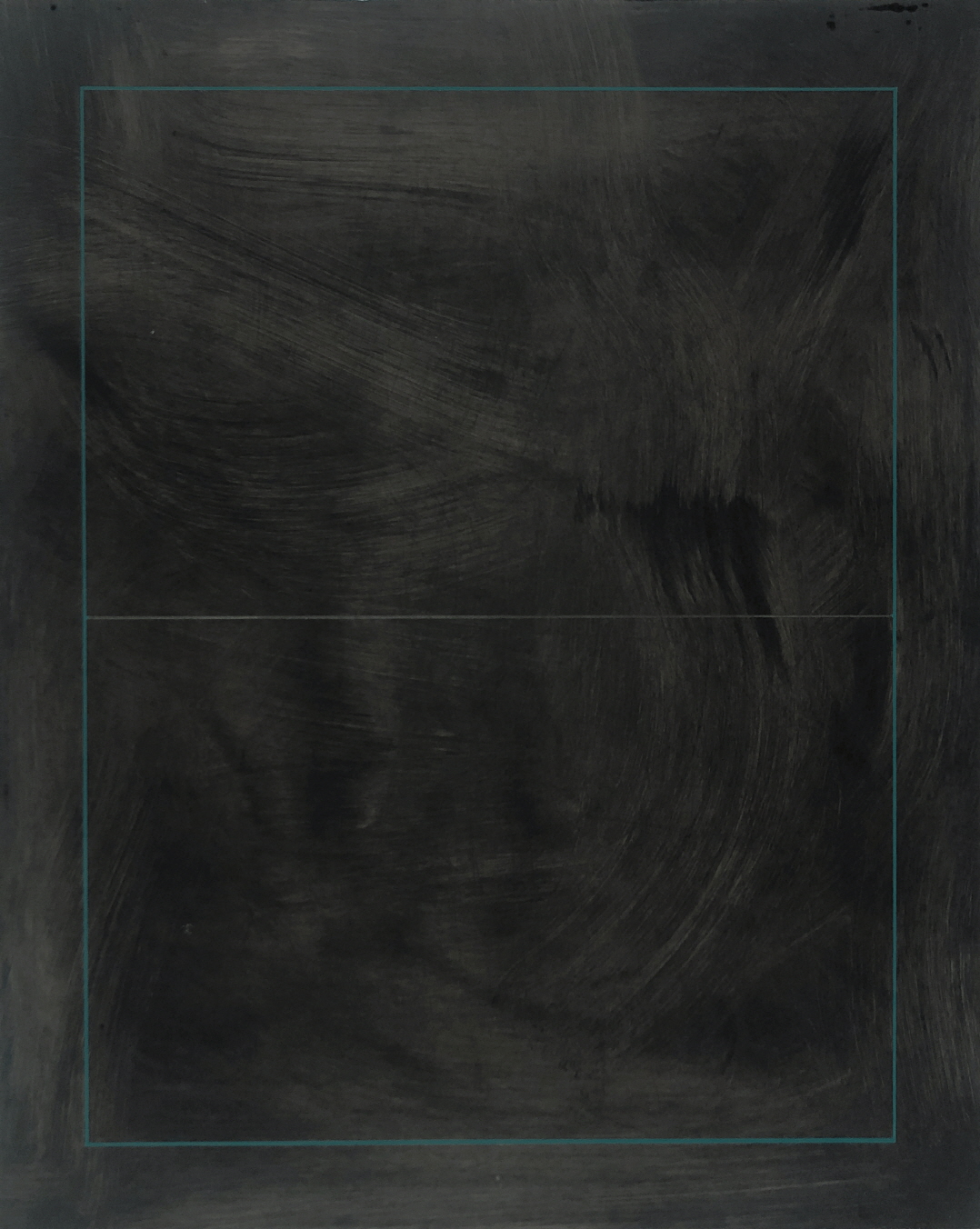

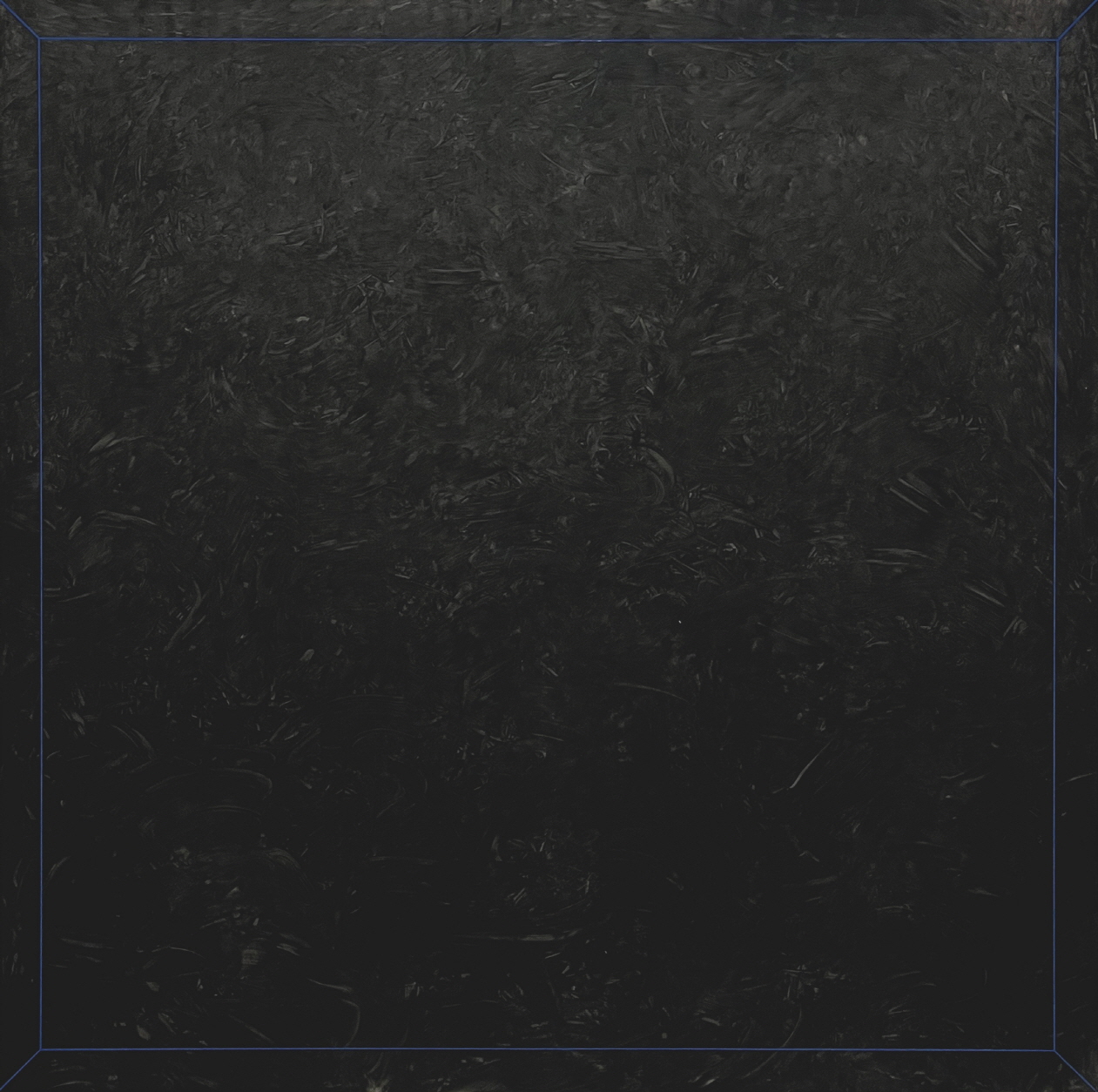

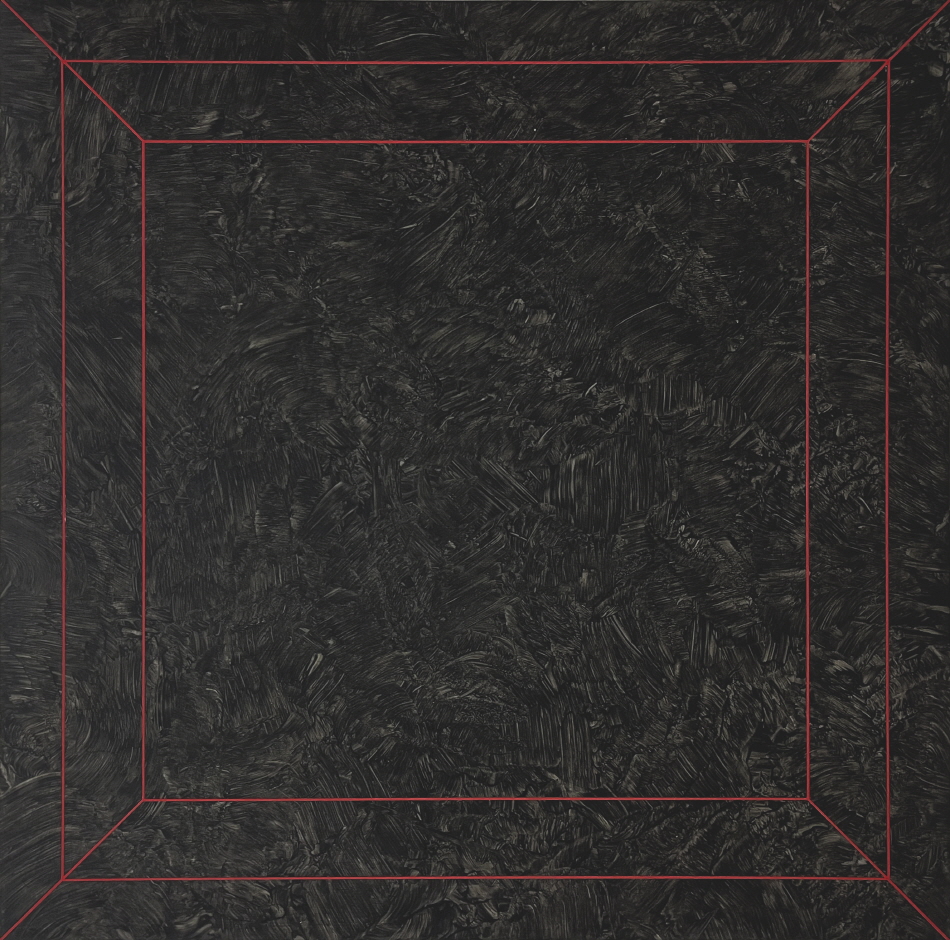

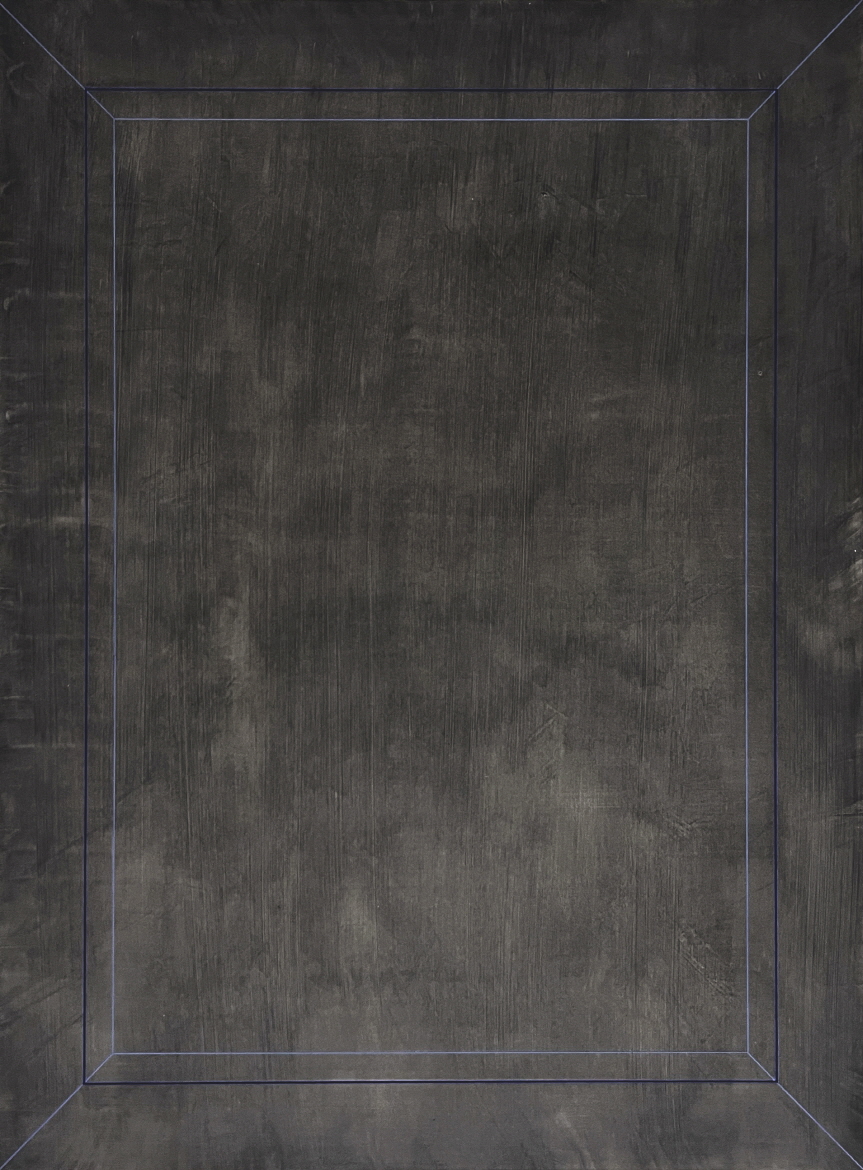

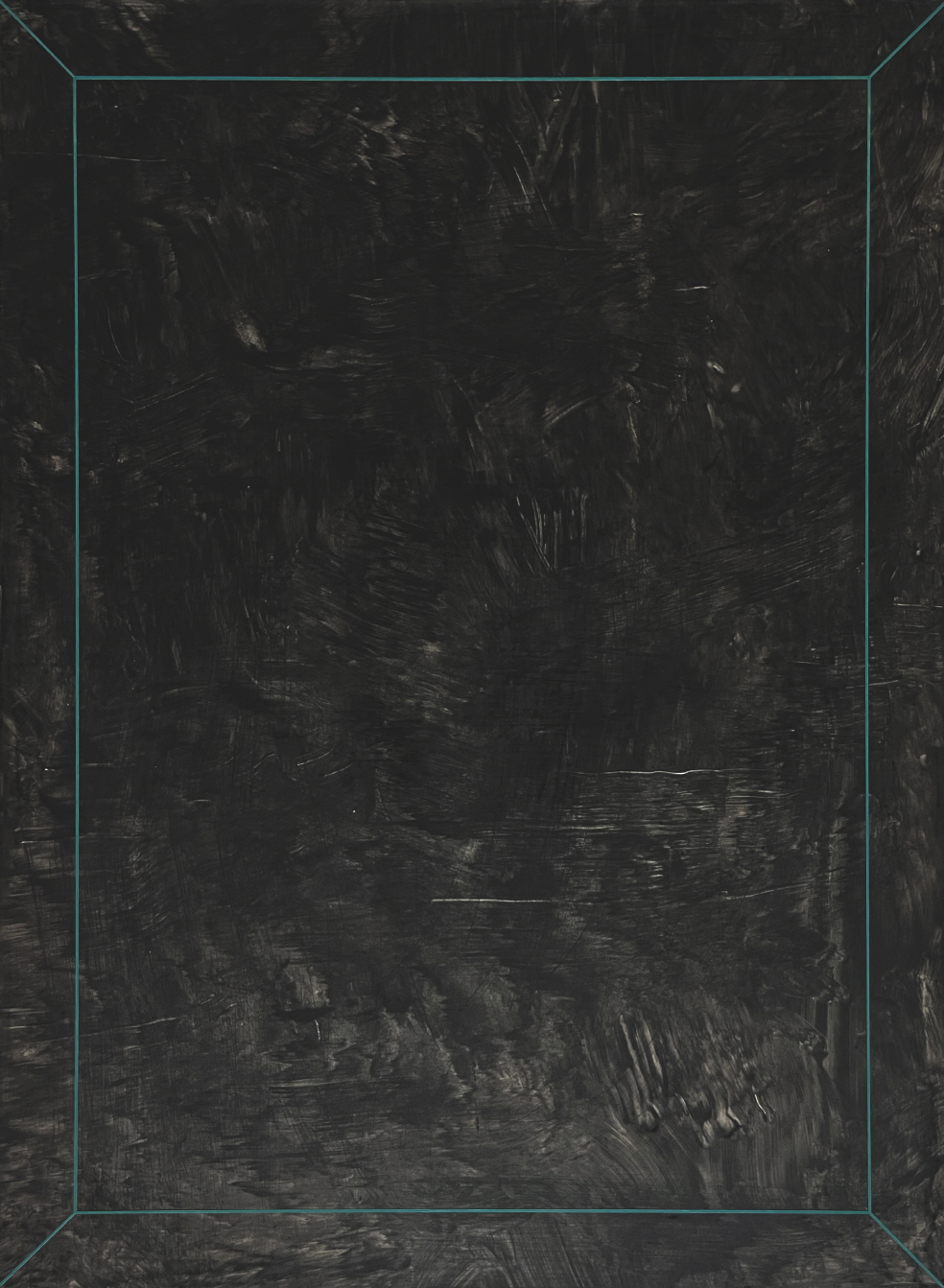

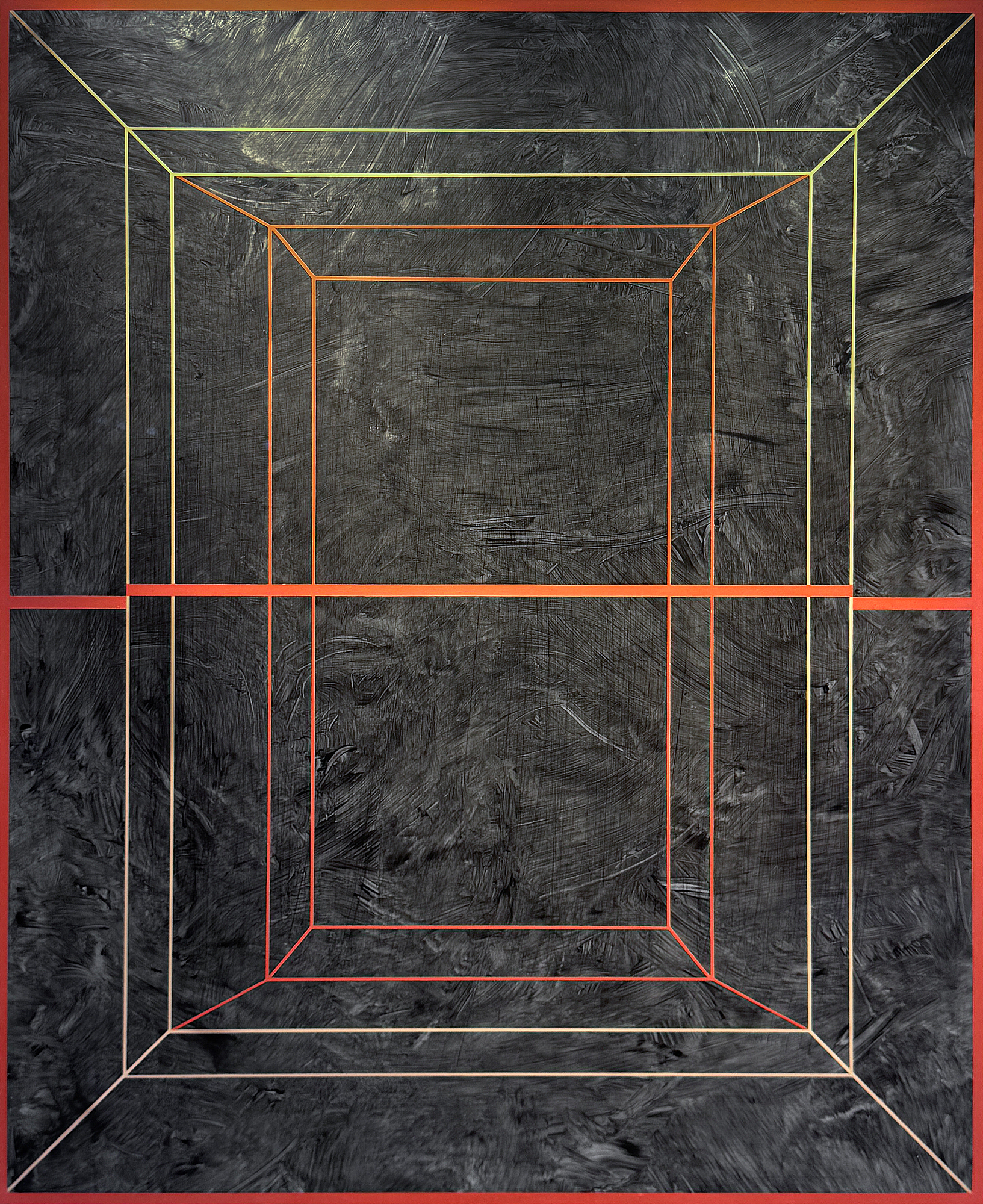

눈앞에 하나의 평평한 회화면이 있다. 더 정확하게 말하면 평평한 것처럼 보인다. 그러나 실은 여러 겹의 석회칠 위에 올려진 먹을 지워간 흔적과 그 위를 뒤덮은 여러 층의 바니시를 다시 직선으로 파내고 안료로 채워진 평평함이기에 불연속적 면이다. 익히 잘 알고 있는 상감기법이 사용되었다. 우리 앞에 그 화면 속 어떤 것도 재현을 의도하고 있지 않다. 먹의 흔적과 여러 색선은 무엇인가를 닮지 않았고 어떤 환영을 일으키려는 목적도 갖고 있지 않다. 다만 긴 시간 속 일어났던 과정들의 흔적을 품고 있을 뿐이다.

생동

2016년 개인전을 앞두고 만났던 작가 이기영은 자신의 작품세계가 자연에서 출발하였으나, 지우기라는 행위를 통해 작품이 작가에 의해 형성되는 단순한 대상이 아닌, 작가 주체와 보다 밀착된 무엇이고자 했고 그렇게 ‘먹꽃’ 연작이 탄생하였다고 설명하였다. 그리고 그 당시 개인전에서 소개된 작품들은 한 단계 더 나아가 먹꽃의 형상이 보이지 않을 정도로 물로 지우고, 다시 지워내며 많은 것을 비워내었기에 영도(zero)에 다가가려는 행위의 결과물로 보였다.

9년 후 다시 만난 이기영의 작업은 이제는 존재와 부재, 질서와 자유, 구조와 해체의 조화로움으로 (또는 긴장으로) 향하고 있었다. 이러한 방향 전환에 따라 작가의 행위, 즉 수행성은 더욱 강화되어 있었다. 다시 그의 작업의 평면을 분석해보자. 그는 감정을 일으키는 순간에 이끌린다. 과거의 기억에서 출발하여 먹으로 쓰거나 그려내고 그것을 다시 손으로 지우면서 어떤 감정이 촉발될 때 몸의 동작을 멈춘다. 이 바탕 작업은 이후 정교한 본 작업 단계로 넘어간다. 작가의 계산된 구상을 바탕으로 여러 개의 색선을 만들게 되는데, 직선을 파내어 안료를 채워넣는 상감기법을 적용한다. 무수한 사포질을 통해 표면은 완전히 연속적인 하나의 면처럼 보이게 된다. 이 본 과정은 생각보다 훨씬 더 세밀함을 요구하기에 신체가 자아내는 긴장감이 작품에 내재하게 된다. 그 선들은 바라보는 위치마다 다르게 보일 수 있도록 정확하게 계획된 위치와 색을 갖고 있다. 관람자가 작품에서 얼마만큼의 거리를 갖는냐에 따라 작품은 계속해서 다른 모습으로 변화하는데, 색선들은 정지된 화면이 아니라 작품이 ‘기운생동’의 구조를 갖도록 고려된 중요한 요소들이다.

열린 변증법

이번 전시에는 이와 같은 방식의 작업들이 20여 점이 소개되는데, 이 작품들에는 질서와 자유, 구조와 해체 같은 대립항이 존재한다. 그리고 그 과정을 통해 절대적 상태로 나아가는 것으로 보인다. 이 대립항들은 서로를 배제하지 않고, 오히려 긴장감을 유지한 채 공존한다. 이 긴장은 화면을 정지된 이차원적 결과물이 아니라, 끊임없이 생성되는 과정으로 전환시킨다. 이러한 과정은 변증법적 운동으로도 해석될 수 있다. 하나의 구조(正)가 화면을 형성하면, 곧 그것은 해체(反)로 향한다. 그러나 두 힘의 흔적은 새로운 합(合)으로 모여진다. 그러나 이 합은 고정된 조화가 아니라, 다시 정과 반의 단계를 거쳐 다른 합으로 나아가는 열린 변증법이다. 이기영의 작품은 헤겔의 정반합을 연상시키면서도, 매번 새롭게 생성되는 과정을 보여준다. 그의 화면은 선형적 발전이 아니라, 반복 속에서 차이를 낳는 유동적 종합과 같다. 그리거나 써진 무엇인가는 지워지고, 파내어진 부분은 다시 채워진다. 감정을 불러일으키기 위한 자유로운 신체 행위의 흔적 위에는 계산되고 긴장감을 머금은 직선이 기하학적 질서를 부여한다. 그러나 그 모든 행위는 평평함, 즉 하나의 평면으로 귀결된다. 그렇다면 여기서 애써 만들어진 평면은 무엇을 의미할까? 여러 단계의 수행적 수고스러움에는 어떤 의미가 얹어질 수 있을까?

절대적 상태로서의 평면

평면은 오히려 입체보다 고정된 현상을 벗어나 자유롭게 상상할 수 있는 가능성을 잠재하고 있다. 평면은 앞서 언급한 것처럼, 절대적 상태이다. 없음, 즉 무로 향하는 것처럼 보이는 변증법적 과정은 실은 생성의 살아있는 단계에 도달하게 한다. 삶이 결국은 생성에서 소멸로 가는 것처럼 보이지만, 삶의 긴 여정 속에 우리는 무한히 많은 새김과 흔적을 남겨 놓는다. 기쁨과 슬픔, 성공과 실패, 만남과 이별 등 인간이 갖게 되는 여러 사건과 감정 그리고 관계와 기억은 개인의 신체와 인간 존재가 거주하는 세계에 각인된다. 이기영의 작업은 정과 반을 거쳐 합에 이르는 과정 속에 만들어지며 그렇게 만들어진 작업의 결과물인 평면 속에 여러 불연속적 면이 있듯이, 최종적인 부재가 곧 존재이며, 소멸이 곧 생성인 것이 곧 삶의 원리임을 깨닫게 해준다.

정소라 (서울시립미술관 학예연구부장)

Journey Toward Creation

Discontinuous Surface

Before our eyes lies a single flat pictorial surface. Perhaps more precisely, it appears to be flat. In truth, however, it is a discontinuous surface where flatness is constructed: the traces of ink disappear into the successive layers of lime wash, followed by the linear incision of multiple layers of varnish on top, and filled with pigment for a texture. It is a well-known inlay technique. The surface before us is devoid of any intention to represent. Neither the traces of the ink nor the chromatic lines resemble anything, and they don’t seem to purpose an illusion. They simply hold the vestiges of processes that have unfolded across a long passage of time.

Saengdong: Life in Motion

When I first met Lee Kiyoung in 2016, he explained to me the genesis of his renowned Black Flower series, that his works, while originating from nature, became somewhat of a personal object through the techniques he applied. In other words, the works transcended being mere objects and became a part of the artist himself. Indeed, the works submitted to his solo exhibitions around that time appeared to have remained faithful to such descriptions: the traces of ‘black flowers’ were washed away with water, erased again and again, until emptied of much, approaching what would be called a state of ‘zero’.

When I revisited his works 9 years later, I found out that his works were oriented toward the harmony – or tension – between presence and absence, order and freedom, structure and deconstruction. This shift has only intensified the artist’s performativity in practices. Let us take this observation to analyze his surface again – he seems to be drawn to moments of emotion. He begins from a memory in the past to write or draw with ink, and erases his work until he finds a certain emotion. Then he stops. This groundwork then transitions into a more deliberate phase of making. Guided by calculated composition, the artist creates several colored lines, employing an inlay technique to inscribe straight lines and filling them with pigment. Through countless sanding, the surface comes to appear as one seamless, continuous plane. This process demands precision far greater than expected, the physical tension of the artist’s body becomes embedded in the work. The lines are meticulously located and colored so that they appear from different perspectives. Because of this characteristic, the work continuously changes its image depending on the distance that the viewer takes. These colored lines are essential elements that allow the artwork to contain a sense of ‘gi-un saeng-dong’, a life force in motion.

Open Dialectic

This exhibition presents about twenty works produced in such a manner. We find binary oppositions of order and freedom, or structure and deconstruction among them. It is through the retained tension between these binary opposites that let them co-exist, and ultimately let the works that contain them move forward to an absolute state. The tension shifts the works from being a static, two-dimensional product to an ongoing process of creating. We may understand this process in terms of dialectic. If the structure that forms the surface is our thesis, the process of erasure and emptying is our antithesis. The traces of these forces on the surface gather into the synthesis. This synthesis, however, is not a fixed harmony; it proceeds once again through thesis and antithesis toward another synthesis, forming an open dialectic. Lee’s works are reminiscent of Hegel in this sense, though his process repeats itself within the dialectical framework. In this sense, Lee’s surface is not a linear progression but a fluid synthesis, producing difference within repetition. What is written or drawn will be erased, and what is inscribed will be filled; on top of the traces of bodily movements that attempt to evoke emotions lie linear lines with tension, ever so calculated and carefully thought out, and eventually impose a geometric order. Yet, all these gestures ultimately resolve into flatness, into a single surface. What, then, does this painstakingly constructed surface signify? What meaning can be ascribed to the laborious, performative steps that bring the surface into being?

Surface as an Absolute State

Unlike the popular misconception that the two-dimensional is more fixed than the three-dimensional, the plane holds great potential for free imagination. As the text has maintained so far, a plane is an absolute state. The dialectical process that seems to move toward absence, toward nothingness, in fact leads us into a living stage of becoming. Life, too, may appear to proceed from generation toward extinction; yet along its long journey, we leave behind innumerable traces and inscriptions. Joy and sorrow, success and failure, encounters and partings – all such events, emotions, relationships, and memories of human existence become etched upon the body and upon the world in which we dwell. Lee Kiyoung’s works are created in the dialectical process, and, much like how several discontinuous planes exist in the surface, they point to us that final absence is at once presence, and disappearance is at once generation. That this is the very principle of life is what Lee’s artworks seem to say.

Sola Jung (Director of curatorial bureau, SeMA)

지우고 채우고, 파내어 설치한 덫

프랑스의 작가이자 미학자 폴 발레리는 「인간과 조개껍질」에서 소라 조개껍질을 손에 쥐고 예술에 대해 사유한다. 외피는 소용돌이 모양의 나선형 구조물을 이루고, 내피는 영롱한 빛을 내는 진주층으로 덮인 연체동물의 거주지. 이 아름다운 자연물은 어떻게 만들어지는가? 특정한 형태를 만들려는 의도에 따라 소재를 선택하고, 도구를 갖고 그를 가공해야 하는 인간의 제작과는 달리, 조개껍질은 연체동물의 유연한 신체조직이 물에서 흡수한 석회질을 발산(emanate) 함으로써 자라난다. 인간의 제작물이 생의 보존이라는 과업과는 독립된 외적 과업의 산물이라면, 조개껍질은 양분과 물을 흡수하여 생명을 보존하는 연체동물의 내적 과업의 산물이다. 시계방향이나 반시계방향으로 회전하는 나선 모양 외피도, “햇빛을 받아 파장마다 빛을 분리해내면서 무지개 빛으로 빛나는” 내피도, 그저 살아있다는 사실로부터만 유래한 결과물인 것이다. 모든 조개껍질이 일정한 형태적 일관성을 유지하기에 이 과정이 무작위적 우연에 의한 것이 아님은 분명한데, 각 조개껍질의 모양과 크기가 서로 다른 건 그 생성이 어떤 기계적 인과성을 따르지도 않는다는 걸 증거한다. 이 점에서 조개껍질은 의도나 기계성, 우연이라는, 인간이 쓸 수 있는 모든 수단을 넘어선 산물이다. 발레리가 지적하듯, 인간은 살아가는 데 필요한 것 이상의 과잉된 능력을 갖는다. 인간은 자신에게 아무 도움도 안 되는 느낌을 느끼고, 삶의 보존에 본질적이지 않은 기관을 가지며, 생명의 보존에 해로운 경우가 더 많은 자유를 갖는다. 살아있는 일이 아름다운 조개껍질을 만들어내는 일과 구분되지 않는 연체동물에게는 ”자기 작품의 소재를 자신의 실질에서 끌어내는“ 일이 가능한 반면, 과잉된 능력을 가진 인간은 무엇인가를 “자신의 존재 전체로부터 분리가능한 정신의 특수한 적용에 의해서만” 제작해야 한다.

그럼에도 우리는 예술이 조개껍질처럼 ”확신에 찬 제작, 내적 필연성, 형태와 소재의 결코 용해되지 않는 상호적인 관계“를 구현하기를 원한다. 우리는 한 작품에 그어진 선이, 조개껍질의 줄무늬처럼, 바로 그렇게 그어질 수밖에 없는 어떤 내적 필연성의 결과면서도, 그것이 자유를 구속하는 기계적 인과성의 결과물은 아니길 원한다. 오랫동안 예술은, 인간이 만든 것이지만 자의적이지 않고, 필연적이면서도 자유로워야 한다는 이 모순된 요구를 감내해왔고, 작가들은 이 자가당착적 과부하를 감당할 자신만의 방법을 창안해왔다. 이기영 작가의 방법은 칸트적이다. 이 작가는 자신의 자유를, 스스로에게 규칙을 부여하는 자기입법(Selbstgesetzgebung)을 위해 활용한다. 그에게 자유는, 지워져 사라질 것을 위해, 스스로의 자유를 제약하는 규칙을 위해 발휘되고, 이로부터 생겨난 긴장감이 시작부터 완성까지 수차례 변신을 거듭하는 작품 제작과정 전반을 관통한다.

소석회를 바른 장지 위를 누군가의 이름이나 문장, 날짜 등으로 채우는 일은 지워져 보이지 않게 될 걸 염두에 두기에 자유롭다. 이를 손이나 대나무 붓, 사포로 문질러 지우는 일은 먹을 작품 표면에 고루 채우는 일이기도 한데, 지우면서 채우고 채우면서 지우는 이 과정을 지배하는 건 우발적으로 생겨난 시각적 혼란을 직관적이고 능동적으로 정리하는, 자유와 형식화 사이의 긴장감이다. 이 양극성이 이루는 긴장 상태를 작가는 ”공중에서 줄타기“에 비유한다. 그 팽팽한 줄타기의 정점에서 멈춘 이미지를 붙들어 매기라도 하듯 그 위에 열세 차례 바니쉬가 도포된다. 각 층이 마르기를 기다려야 하기에 적어도 열흘 이상의 시간이 걸린다. 이 시간 동안 묵혀진 그림은 가장 긴장되는 다음 공정을 위해 수술대 같은 작업대에 놓인다. 예리한 칼로 바니쉬 층에 깊고 날카로운 선을 새겨넣기 위해서다. 자칫 칼이 빗나가기라도 하면 지금까지 모든 과정이 무화될 것이다. 그렇게 생겨난 깊고 강렬한 긴장감을 내포한 이 선은 처음에는 먹빛 화면에 묻혀 보이지 않는다. 파인 부분을 밝은색 안료로 채워넣고 광택이 없어질 때까지 그림 전체를 그라인더로 갈아내고 나서야 비로소, 말 그대로 그림 속에 삽입된 가느다란 색 선이 보일 듯 말 듯 떠오른다. 가늘고 정교하게 새겨진 색 선은 전반적으로 어두운 작품에 순간적인 색감을 부여해 그림을 더 가까이에서 들여다보도록 유혹한다. 적절하게도 작가는 이 선을 ‘덫’에 비유한다. 그림 속에 숨어 우리를 그림 속 ‘공중 줄타기’에 올라 흔들리도록 하는.

김남시 (이화여대 조형예술대학)

Traps Set by Erasing, Filling and Carving

In Man and the Seashell, French writer and aesthete Paul Valéry meditates on art with a conch shell in his hand. The dwellings of mollusks with an outer shell of a spiral structure and an inner shell covered with an iridescent layer of mother-of-pearl: how is this beautiful natural object made? Unlike a human product, whose materials should be selected according to an intention to make a specific shape and which must be processed by tools, a seashell grows as the mollusk's flexible body tissues emanate the calcareous components absorbed from the water. While human artifacts are the products of external tasks independent of the task of preserving life, shells are the products of the internal tasks of mollusks to preserve life by absorbing nutrients and water. The spiral-shaped outer crust that rotates clockwise or counterclockwise and the inner crust that “glows in the iridescent light as it receives sunlight and separates the light at each wavelength” are simply the results of the fact that they are alive. Considering that all shells maintain a certain morphological consistency, it is clear that this process is not due to random chance. The different shapes and sizes of shells testify that their formation does not follow any mechanical causality. In this regard, the shell is a product that transcends all human means such as intention, mechanical properties, and contingency. As Valéry points out, humans have an excess of abilities beyond what is necessary to survive. Human beings have feelings of no benefit to themselves, have organs that are not essential to the preservation of life, and have freedom which is frequently detrimental to survival. For a mollusk, whose subsistence is indistinguishable from the formation of a beautiful shell, it is possible to “draw the subject matter of its work from its own substance,” whereas a human being with an excess of ability must produce something "only by the special application of a mind which is separable from the whole of his being."

Nevertheless, we want art to embody “a confident production, an inner necessity, a never-dissolving mutual relationship between form and material” like a seashell. We want the lines drawn in a work of art to result from an inner exigency of needing to be drawn only that way, just like the stripes on a seashell. And yet, we do not want them to result from mechanical causality, which binds freedom. For a long time, art has endured the contradictory demand that, although man-made, it must not be arbitrary but necessary and free, and artists have devised their own ways of coping with this self-contradictory overload. Kiyung Lee's method is Kantian in nature. He uses his freedom for self-legislation (Selbstgesetzgebung), imposing rules on himself. Freedom, for him, is exercised for the rules that constrain that very freedom, which govern things that will be erased and disappear. The tension deriving from this runs throughout the entire process of the piece going through a number of transformations from start to finish.

The act of filling the surface of jangji (a type of thick, high-quality traditional Korean paper) coated with slaked lime with a name, sentence, or date is unfettered, performed with the knowledge that they will be erased and become invisible later on. To remove these by hand, bamboo brush, or sandpaper is also to evenly fill the surface of the work with Chinese ink. What is dominant in this process of erasing while filling and filling while erasing is the tension between freedom and formality, which intuitively and proactively organizes the accidental visual chaos. The artist compares the tension created by this polarity to “tightrope walking. In the air.” Varnish is applied thirteen times on top of the image as if to fix it at the apex of a tense tightrope. It takes at least ten days since he has to wait for each layer to dry. Then, the painting is placed on an operating table-like workbench for the next, most stressful, process: to carve deep, sharp lines into the varnished layer with a sharp knife. If the knife goes amiss, all the process up to that point will be in vain. The lines, which contain the deep and intense tension thus created, are at first invisible because they are buried in the surface of the painting drawn in Chinese ink. Only after filling the scraped places with bright pigments and grinding the entire surface of the painting with a grinder until it loses its luster do the thin colored lines literally inserted into the picture become visible to the eye. The fine, elaborately carved lines tempt us to take a closer look at the painting by giving a momentary flicker to the overall dark work. Appropriately, the artist compares these lines to "traps" which hide in the picture, making us climb on the "tightrope" and sway in the painting.

Namsee Kim (College of Art & Design, Ewha Womans University)